Part 1

The philosopher and the psychologist are at a cafe. One person has written about how we ought to behave without any reference to how we are - the other person has written about how we are without trying to say anything about how we ought to behave. Doesn't this seem strange to you? It does to me. So let me try to help.

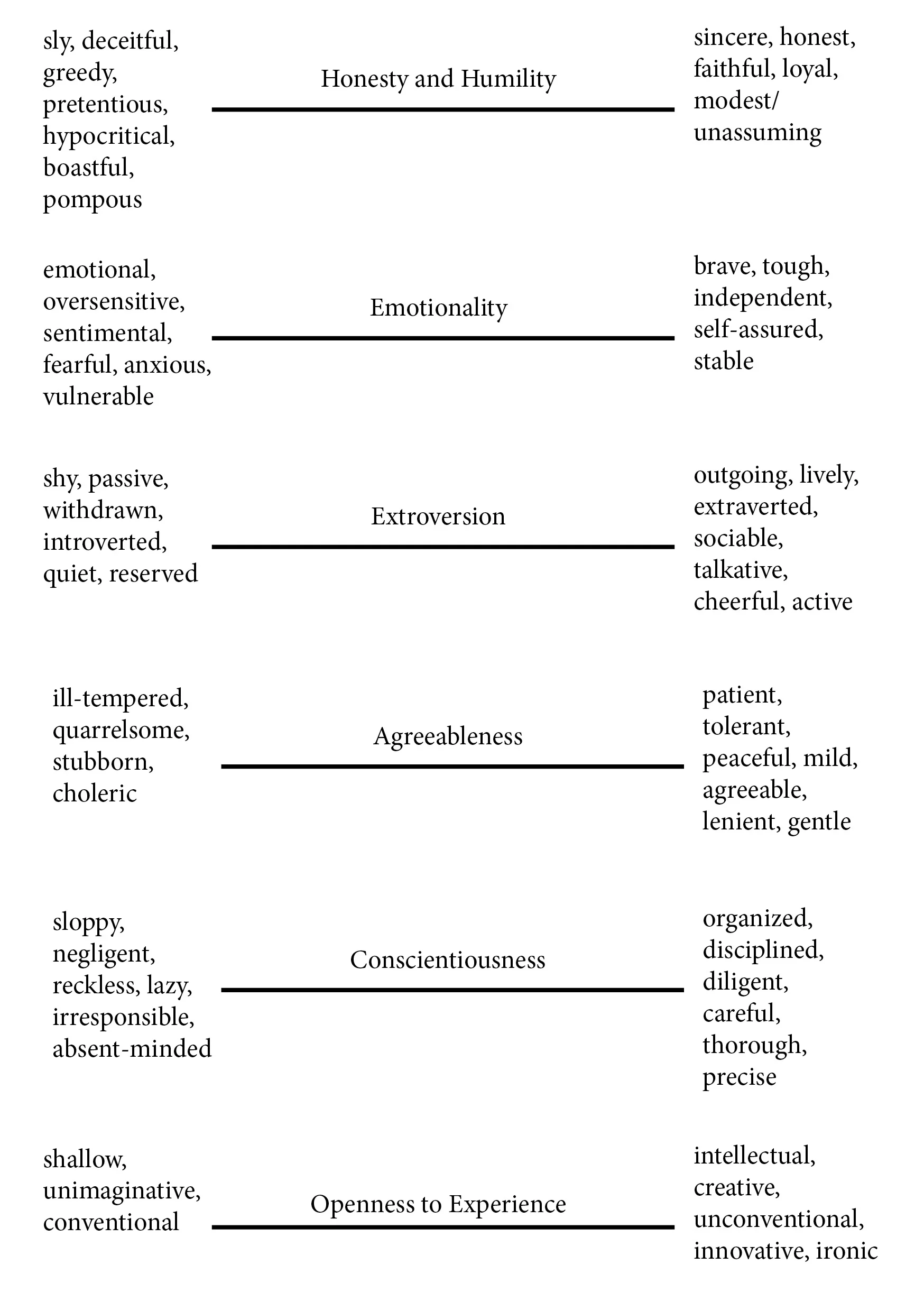

Let us start with the are's before we go into the oughts. The dominant model of personality right now is the "Five point personality trait" model; but we are going to use a slightly updated version of six traits. This model was established by doing a statistical analysis on the collective vocabulary, and sort of finding out which words that more or less described the same thing.

The six different traits are: 1. Honesty/humility 2. Emotionality 3. Extraversion 4. Agreeableness. 5. Conscientiousness and 6. Openness to experience.

These are helpfully arranged along a single dimension.

To me, this list is provocative. My inner being resists being reduced to six different dimensions of personality. Should it? Yes and no. This list of traits does not reduce who we are. It does not try to describe all of who we are, or what is interesting about us. It is simply a tool for understanding facets of a personality. And with that caveat, let us have a close look at it to see if it can be used as a tool for right conduct.

What immediately jumps out at me are three traits that are more directly moral than the others; Conscientiousness, Agreeableness and Honesty/Humility. The words within these categories are judgemental words; they imply if we like a person or not based on if we assign them these qualities. So, for instance, on the Agreeableness-scale; on the one sinister side we find ill-temperedness, and on the right side we find patience.

How do we know that these are moral ideas? We can find it in our emotional response to the idea of meeting such a person. If given a choice, and you knew nothing else about this person; would you rather meet the patient person or the ill-tempered one? I think most of us would go for patience.

In the other categories; openness to experience, emotionality and extroversion, it is not so clear to me that one is morally better than the other. Do we pass more of a judgement on someone who is passive and reserved, versus someone who is talkative and cheerful? Maybe we do, maybe we don't - I think that is an empirical question. Either way my intuition does not give me any preference, and in this instance I will trust it.

These scales are social, because these words are used to describe relations among people. Honesty and conscientiousness are character traits which only gain saliency when other people are forced to relate to us a such.

For these three dimensions, then; conscientiousness, honesty/humility, and agreeableness; I think one would overall be a more moral person if one aspired to be conscientious, honest and agreeable, in many of the facets which are described.

This scale is not perfect, it does not cover all morality, and the values are socially determined, to a degree; not perhaps so much in what they are, but what the ideals of a society are. Non thesless, I think learning about these scales can be an important way to look at a facet of morality. And why do I think this? Because I myself have learned something.

I am an agreeable person, and I try my best to be an honest person. But where I am not, to the extent I wish to be, a conscientious person. I have been, and must be careful not to be negligent, irresponsible and absent minded. And I need practice in being diligent, disciplined and through - which makes me sad to even think about. It is something I have known about for some time, and is striving to rectify, even little by little - but learning of this psychological characterisation has made me more aware that some of these traits of mine have been part of a similar phenomenon.

Changing one's personality takes a lot of hard work, but I don't think it is impossible. And, things are also not clear cut always. My absent-mindedness has not meant that I have not been thinking, it as more often meant that my interests have been pulled in many directions; and as a result, I have learned a lot from many different fields. But too often, this has come at the cost of something else that was important.

Part 2

Many years ago I wrote a blog post about some small rules for moral conduct. I now want to look at the six part scale versus the rules I came up with then to see how they compare. This is the sextette ruleset I made back then:

1: Try to know the difference between doing good and doing bad. Try to do good.

2: Try to know the difference between truthfulness and deceitfulness. Try to be truthful.

3: Try to find out what is valuable, and what isn't. Cherish that which is valuable.

4: Respect the personal integrity of others. The different kinds are; of feelings, of opinion, of wishes, of promises and of identity. Respect someones lack of integrity enough to tell them.

5: Hold that a disagreement is not an opportunity to engage in verbal warfare, but a chance to learn the thoughts and arguments of others - from which you can revise your opinion.

6: Treat others as you think they wish to be treated, let them respectfully know how you'd like them to treat you.

It is interesting to see that these rules so closely follow my own personality. The things that are emphasized here are honesty, humility, and agreeableness. There is only one point here that has to do with conscientiousness, and that is that we should respect the integrity of someone's promises. That is, we should treat them as responsible to their word, and hold them accountable on what they promise to do.

In retrospect I like the idea of "trying to do" these things. It respects the fact that we are all fallible.

There is also point number three about value. That point is absent from the personality test, and that is because value is not defined by our personality, but by our appreciation. That is, our ability to set the value of things. This rules says that, when something is of value, we should respect it. If someone has written a book, for instance, we ought to evaluate it to see if it is a book that contributes to the welfare of people as a whole, and if it does, accord it some measure of value, so that we keep adding value to our society, make us all richer. This value accretion must then be in relation to our society, all society in general or nature, or at least some higher goal. Destructive behavior and devaluing of important things degrade the wealth of our society, which I think is a bad thing to do.

The reason I think this dimension is not covered by the personality trait is that it springs from a socio economic understanding of society, which I think is not part of common parlance. I think we can still find it here and there, but then as moral attitude which, when taken together and in their consequence will achieve some of the same result; such as carefulness, modesty and activeness.

If I were to revise the rules as stated above, I would include one or two around the conscientiousness dimension - but it's not easy. One cannot simply write "Try to keep your promises." What if you promise to do something bad to someone? Or what if your promises compete with something else that is equally important? There are two aspects of conscientiousness that make it more difficult to implement. Firstly, one cannot know what the future will bring; so any promise will have to be given with the caveat "to the best of my ability, and not exceeding normal expectations for what is sound in my concurrent dealings..."which sounds a bit cumbersome. And secondly, at any point, you will most likely have many different duties, and it will be your task to choose among them.

Maybe I feel bad about my ability to be conscientious has to do with some of these types of issues, or maybe I have these kinds of issues because I am not very good at it. Either way, I don't feel ready to say much more about it now. These things, I've understood, take time.